If I could be an effective evangelist for something secondary to the good news of Jesus, it would be Hadestown. I find it difficult to describe the show in a way that makes people who aren’t lovers of Greek mythology or musical theater want to experience it, but I truly believe it is beautiful and everyone should get to experience it. Hadestown is a captivating show, made beautiful by its genius lyrics, symmetrical music, and heartbreakingly hopeful characters. I loved listening to the album, and I’ve watched plenty of YouTube performances of the main songs (plus a bootlegged video of the original cast…), but nothing compared to seeing it in person.

Quick explanation of Hadestown: it’s a musical about two Greek myths, Orpheus and Eurydice, and Hades and Persephone. Two tragic love stories. Hades is god of the Underworld and everything under the earth, including gold, silver, and the dead. He falls in love with Persephone, daughter of Demeter goddess of the harvest and fertility. Depending on the story, Persephone is sometimes portrayed as seduced by Hades and sometimes equally in love, but in any case, he convinces her to be his queen and come down with him to the Underworld. However, she misses the upper world, the sun, and all living things though, and it misses her in return, so they make a deal that she can live in the sun for half of the year and with Hades for the other half. This creates seasons; when Persephone is traveling up, spring comes and prepares for her arrival, then the world rejoices in the summer sun. Then the harvest comes and things begin to die as she leaves, and the world waits in winter for her to come back and renew the cycle.

Our other couple is Orpheus and Eurydice. Eurydice dies (bitten by a snake in the original myth) and is taken to the Underworld. Orpheus, a poet and singer, journeys to the Underworld to get her back, finding his way through his song. When he finds her, he sings a song of his love so beautiful, it convinces Hades to let her go. But, he doesn’t make it easy. They have to walk out again, Orpheus in front and Eurydice behind. If he turns back to make sure she is with him, she will be taken back and he will have to wander between the world and the Underworld forever. He was meant to trust in his love, but it’s a tragedy, so right before they get to the sunlit land, he turns back, and she is lost to him forever.

In the story of Hadestown, the love stories are paralleled, and Orpheus’s song not only convinces Hades of Orpheus’s love for Eurydice, but also makes him fall back in love with Persephone. Part of the conflict of Hadestown is that the world is not right because Hades and Persephone have forgotten their love. Hades is jealous of Persephone’s time in the sun, so keeps her longer and makes the winter longer. Persephone resents her time with the dead and drowns her frustration in a river of wine, there’s no more spring or fall, and even summer is miserable because it’s too hot. Orpheus sees this and takes it upon himself to save the world by beauty, which he does, but sadly dooms his own love in the process.

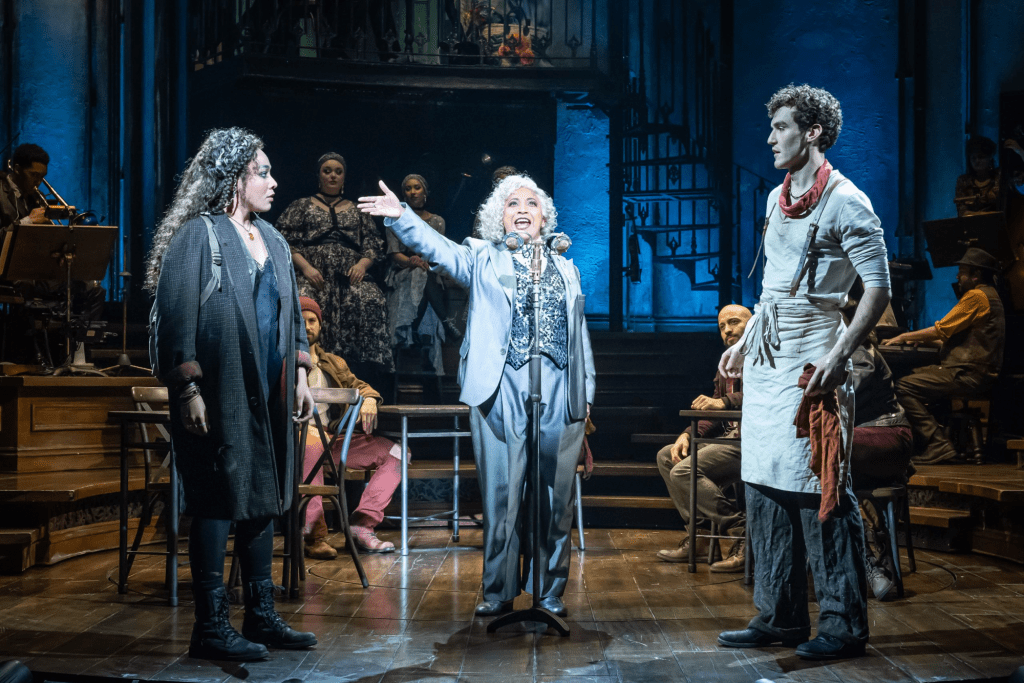

Lest you hear Greek myth and think of togas, columns, and lyres, the show is set in an ambiguous time and place, and the music is a folksy jazz style. It’s Depression-era inspired, but Eurydice has that grunge look of the 90s/00s, Hermes (the storyteller) wears a clean cut sharp silver suit that would look at home in the 50s/60s. Hades wears a pinstriped suit of a railroad tycoon in the 20s/30s, and Persephone’s dress might be mistaken for that of a 40s club singer or Dolly Parton. The Chorus would look at home a hipster Portland coffee shop/brewery. From the beginning trombone notes, your feet are tapping and your head is bobbing as you’re invited into the rustic bar scene. When Orpheus brings out his electric guitar, you’re swept away by the romance and yearning that calls you home, the feeling both familiar and strange. Then, when the stage expands as Hades and Persephone descend back to the Underworld, you’re almost blinded by the unnatural brightness and feel the pounding of the syncopated industrial beat in “Chant”.

In some ways, it’s such a simple story with simple sets and costumes, but as the turntables of the stage go round and round and the themes and melodies repeat themselves in your mind, its depth and beauty draws you in. Seeing it in London was especially fun because the voices of the actors, though different to what my ear was used to from the original cast recording, sang out in their own accents and tone, adding to the idea that the time and place setting is unimportant to story. It’s outside of time and place, so we are fully drawn outside of our own time and place into the world of Hadestown, but the boundaries are permeable. When the curtain falls, we land back in our own world, but when we are invited to raise our cup at the end, we know they will sing it again and again (literally, 8 times a week). “Goodnight brothers, goodnight,” the haunting last words of the show, is an acknowledgment that the sun will rise again, and with it, the start of the old song. Days, seasons, years turn back on themselves with comforting invariability. If I could afford to see it over and over again, I would. Even so, it will live on in my memory.

However, that doesn’t mean everything will stay the same. The world is as it is, but the poets and lovers open up our vision to see the world as it could be, when it is in love.

One question repeats itself as I left the theatre: Why does Orpheus turn around?

If he was so in love with Eurydice, enough to journey to the Underworld and walk almost all the way back out, why turn around at the very last moment? The whole story, he never doubts her love. She pushes him away at first, falling in love “in spite of herself,” but he is always there gently pursuing her and drawing her into his safe embrace. My theory: he turns because he doubts his own ability to sing the world back into right turning. It’s self-doubt.

In “Doubt Comes In”, he doesn’t ask himself, is she there, (the fates ask where is she); he asks “Who am I to think that she would follow me into the cold and dark again?” and “Why would he let me win, why would he let her go?” Is this a trap or a trick? It echoes his original question in “All I’ve Ever Known” from Act 1, “Who am I that I should get to hold you?” The only reason he was able to convince Hades to let her go was his song, which reminded Hades of his love and softened his heart towards mercy, so Orpheus doubts that his song was enough, that it was a trick all along, that he does not belong there. Writing the song was the reason he lost Eurydice in the first place; Orpheus was so engrossed in the song did not hear her cry out to him nor see her fear of the approaching storm and their lack of shelter. Eurydice’s bravery to walk the long road was never in doubt for him. He said himself he held the whole world when he held her in his arms, but can he actually hold the world? Can he shelter her and make a home for the wanderer always swept up in the changing wind?

Clearly, self-doubt blinds and binds us more than distrust in others. It makes us think we are alone, but if we listened to the voice of those we love, we would know, “you are not alone, I am right behind you, and I have been all along.” The dark will not last, and the sun will rise again. All we have to do is keep walking, keep trusting, keep loving.

If the love stories are parallel, could the same be true for Hades and Persephone? Hades might be the end product of Orpheus and Eurydice, if they were gods. Hades doubts that Persephone will come back to him so his work to impress her and fill the gap she leaves consumes him. He knows his kingdom is nothing compared to the world of summer and sun and harvest, so the only thing that could bring Persephone back is love of him. It pushes her away though, and she is repulsed by his Electric City because she knows, despite his assurance that he created it for the love of her, he has created it for himself. She doesn’t want a power grid, bright and unnatural as a carnival, she wants the sun, and he missed it because he is blinded. They are stuck in the cycle, rotating further and further apart from each other.

Thankfully, Hades and Persephone, and the rest of the world, are saved most unexpectedly by a poet. The circle corrects itself, but at the cost of the poet’s love. Tragic. And we sing it over and over again, hoping this time he’ll reach the sun and lead Eurydice into the light. Of course he doesn’t, but its written so well that as the music swells and the stage spins, you really do believe they’re going to make it.

But… I do believe there is a hopeful moment, leading us to hope that maybe the song, the internal one being sung by players as opposed to the meta-story, will change at the end. The Fates can be proven wrong. After the weeping and the silence, the stage is reset, and all the characters come back on stage in their original costumes. And, as Hermes sings, Orpheus the bartender and Eurydice the wanderer catch each other’s eyes in their own spotlights, both as if meeting for the first time (“and I don’t even know you yet”) and as long lost lovers (“as if I knew you all along”). They’re ready to start the song over from the beginning, literally for the next performance in a couple hours if you’re catching the matinee, but I think this brief moment is also to give the audience and players hope that the story continues. Maybe they find each other again, in the same way that Persephone and Hades get to start over. In a lovely parallel moment, as Persephone heads back to the world on top, she asks Hades to wait for her, who promises “I will.” Maybe Eurydice doesn’t forget Orpheus or herself like she did at first, maybe the vision of the better world and his song will carry him on. Maybe his song changed things, and even if they are apart for a time, she will wait for him, and he will find her again. Maybe they can still keep to their promises and walk home together.

It’s an old song, it’s a sad song. But we’re gonna sing it again and again. And when it’s finished and when we sing it, spring will come again.